Share your feedback with us on the draft Ōtūkaikino Stormwater Management Plan.

Share this

Consultation has now closed

Consultation on the Ōtūkaikino Stormwater Management Plan has now closed. People were able to provide feedback from 7 March 2023 to 2 May 2023.

During this time we heard from 1 community board, 2 organisations and 3 individuals. You can read their feedback [PDF, 132 KB](external link) and also find out how this influenced the Council decision.

You can read the meeting minutes(external link)(external link) which include the formal resolutions. You can also watch the decision being made.(external link)

A stormwater management plan sets out the ways Christchurch City Council will meet the requirements of its stormwater resource consent, which was granted by Environment Canterbury in 2019. This 25-year resource consent is called the Comprehensive Stormwater Network Discharge Consent (CSNDC). Its purpose is to improve surface and groundwater quality and address problems caused by the nature of stormwater discharged into waterways. It promotes water quality improvements over time in order to meet targets in the Land and Water Regional Plan.

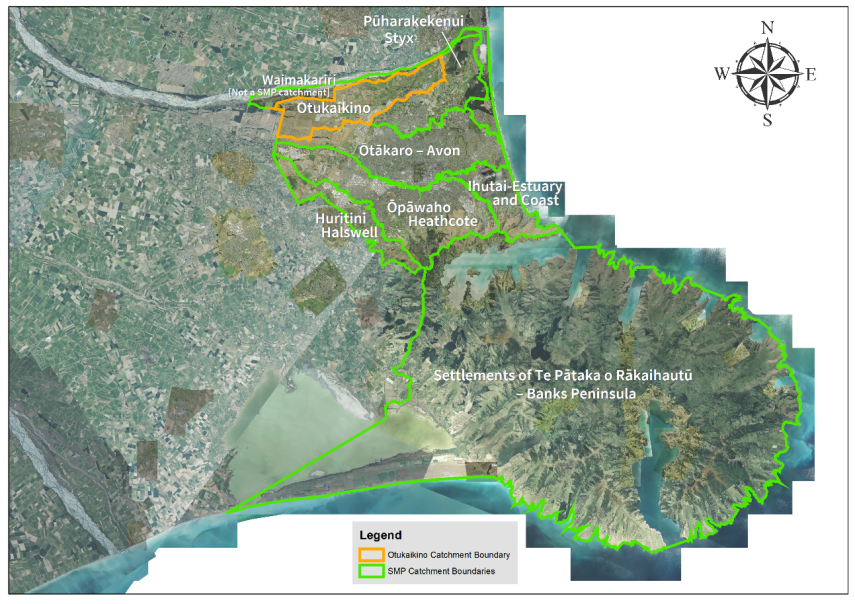

The Ōtūkaikino catchment covers an area that, until the 1930s, was the old river bed of the main (south) branch of the Waimakariri River. The catchment lies north of Johns Road, from Chattertons Road to the Main North Road and Chaneys Road intersection. This area is 6,200 hectares.

The Ōtūkaikino Creek and several other streams flow all year round, fed by water from the Waimakariri River. The eastern parts of the catchment are drained by pipes and drains, but rainfall and stormwater from the western half of the catchment drains into the ground, which is gravelly and porous. The Ōtūkaikino Creek and its tributaries have the best water quality in the city.

Belfast, part of Chaneys, McLeans Island, and Coutts Island are all located within the Ōtūkaikino catchment area.

Purpose

The Ōtūkaikino Stormwater Management Plan has three key purposes:

- To propose targets for lowering stormwater contaminants

- To describe the ways stormwater discharges will be improved over time to meet environmental objectives.

- To discuss how flooding risks will be dealt with, if there are any.

Summary document [PDF, 895 KB]

Draft of the Ōtūkaikino Stormwater Management Plan* [PDF, 3.2 MB]

*Please note the full plan was updated on 29 March 2023, with corrections to Section 10.3 and Table 9

Ōtūkaikino stromwater catchment area

Water quality and ecological health

Most Ōtūkaikino waterways are in rural parts of the catchment and don’t face the same issues as urban streams and rivers throughout the city.

Stormwater runoff from the western part of the catchment goes into the ground either naturally or via private facilities, while, stormwater runoff from the eastern part of the catchment enters the Ōtūkaikino Creek near Belfast.

The ecological health of the Ōtūkaikino Creek is classed as “good” and the creek is relatively free from the contaminants, aside from those typically linked to agriculture.

It’s important that we future proof the stormwater network to support increasing residential development in the catchment area so that stormwater is adequately treated before being discharged into waterways.

The draft Stormwater Management Plan for Ōtūkaikino proposes that all stormwater will be treated through basins and wetlands, or infiltrated into the ground. Treatment basins and wetlands don’t remove all contaminants from stormwater, so the Council will need to monitor the condition of the creek for changes.

Flooding risks

The geography of Christchurch makes it vulnerable to flooding and stormwater management plans are an important tool for managing the effects of flooding on residential, commercial and industrial areas.

Urban parts of the Ōtūkaikino catchment are protected by a stopbank along the south bank of the Waimakariri River. It is known as the primary stopbank. A secondary stopbank runs along the edge of the urban area. Both are maintained by Environment Canterbury.

Residential, commercial and industrial land along Johns Road and in parts of Belfast sits above the anticipated level of flooding from the creek, providing protection and adequate drainage for stormwater. Localised flooding is possible in some of the low-lying parts of Belfast. The Waimakariri Stopbanks reduce the impact of extreme flooding and would provide protection if the Waimakariri River breached its banks.

While the Council doesn’t currently need to manage flooding in the Ōtūkaikino Creek, the draft Stormwater Management Plan considers the way we manage surface flooding to enable development to continue safely.

Values

Water is a taonga (a treasured natural resource) and represents the lifeblood of the environment for tangata whenua. A relationship with the environment is central to Māori creation stories, spiritual belief, and ways to manage resources. Land, water and resources are a statement of identity. In a particular area, they relate to a group’s origin, history, and tribal relationships. The whakapapa of a waterway would determine its use in tohunga (spiritual), waiwhakaheketupapaku (burial sites), waitohi (spiritual use), waimataitai (coastal mix of fresh and salt water, estuaries), waiora (spiritual healing water), and mahinga kai (food gathering).

The maintenance of water quality and quantity is perhaps the greatest resource management issue for tangata whenua.

All waterways are a major feature within the landscape and should remain unchanged. Culturally, all waterways are significant and come together as one. Waterways begin as rain drops and connect together as streams, lakes, estuaries, and wetlands, all leading to the sea.

Ōtūkaikino

The Ōtūkaikino Creek formed along the old river bed of the Waimakariri River. The Waimakariri River, is one of the largest rivers in Canterbury and until the 1930s, the main branch of the river ran through the Ōtūkaikino catchment.

Historically, the Waimakariri River is highly significant to mana whenua, as it is associated with many mahinga kai sites, urupa, kāinga and kāinga nohoanga. The name Ōtūkaikino also refers to a protected wetland reserve to the east of the waterway, which has been designated by mana whenua as a traditional wai whakaheke tūpāpaku (water burial site).

A cultural health assessment of this catchment was carried as part of the 2022 mātauranga monitoring report. The monitoring indicated that the catchment is in moderate cultural health, with sites where extensive restoration works have been undertaken scoring the highest. Over the years the catchment has been highly modified from a braided river to a low plains spring-fed stream and adjacent agricultural land uses and roads were identified as the largest pressures on site health.

What we know about sediment

- Road wear and vehicle tyres are believed to be a major source

- Therefore stormwater discharges are a significant source

- Construction is a source

- Pastoral activities are a source

- Deposits from the atmosphere are a moderate source

- Stream-bank erosion may be a source.

What we know about copper

- Vehicle brake-pads are a major source of copper

- Copper in rainfall contributes

- Soils are a minor to moderate contributor

- Small changes in the number of copper roofs can affect copper concentrations in stormwater

- Products used to clean roofs and pathways may contribute.

What we know about zinc

- Roofs are the source of maybe 65-70 per cent

- Tyres are the source of maybe 25-30 per cent

- Other zinc-coated steel items (fences, ventilation ducts, poles) may produce 1 to 5 per cent

- House & garden products (moss control) make some contribution.

- Soil contributes to a small extent.

Our goals are:

- To ensure the quality of stormwater from all developed areas is treated to best practice.

- To have 100 per cent of stormwater treatment facilities built and operating to Waterways and Wetlands Design Guidelines standards.

- To have less than 5 per cent of all consented construction activities reported non-compliant due to sediment discharges – by 2025.

- To investigate ways to reduce the environmental effects of sediment discharges – by 2023.

- To look at options for carrying out street sweeping, sump cleaning, and send-to-wastewater trials – in 2022/23.

Recommended for the Surface Water Improvement Plan

Reduce road sediment by the best practicable option determined by the results of street sweeping, sump cleaning and trialling alternative treatments.

Our goals are:

- To have 100 per cent of stormwater treatment facilities constructed and conforming to Waterways and Wetlands Design Guidelines standards.

- To investigate zinc mitigation measures and carry out cost/benefit analyses toward identifying their effectiveness as best practicable options – by 2023.

- To consult with key stakeholders and identify a long-term zinc strategy in line with current technologies – by 2025.

- To collaborate with local and regional government in a joint submission to central government seeking national measures and industry standards to reduce the discharge of contaminants from buildings and vehicles.

Recommended for the Surface Water Improvement Plan

- Adopt a strategy to limit zinc, based on finding the best practicable options.

- Research and trial ways of trapping roof-sourced zinc on-site.

Our goals are:

- To consult with the Government, through the Ministry for the Environment, about legislation to limit the copper content in vehicle brake-pads.

- To not permit stormwater discharges into the network from unprotected copper building cladding, spouting or downpipes.

- To investigate a District Plan rule to discourage the use of copper building claddings.

Our goals are

- To compile a database of industrial sites considered to be medium or high risk based on the best available information – by 2025

- To audit high-risk industrial sites by the approved procedure under the Comprehensive Stormwater Network Discharge Consent.

Our goals are:

- To work with community groups to educate participants about current stormwater practice and to enable the public to take action to stop contaminants at source – by 2025.

- To engage regularly with the Ministry for the Environment to collaborate on initiatives to reduce contaminants – by 2025.

Our goals are

- To limit the quantity of stormwater from all new development sites to pre-development levels, and minimise stormwater increases from re-development sites through consent conditions.

- To protect houses from flooding during and after development by having controls on new floor levels.

- Continue to improve flood models and our knowledge of flood risks.

Speak to staff about the Plan

Please get in contact if you would like us to attend a meeting to discuss the plan and answer any questions you may have.